Responses to the Problem of Drug Dealing in Privately Owned Apartment Complexes

Your analysis of your local problem should give you a better understanding of the factors contributing to it. Once you have analyzed your local problem and established a baseline for measuring effectiveness, you should consider possible responses to address the problem.

The following response strategies provide a foundation of ideas for addressing your particular problem. These strategies are drawn from a variety of research studies and police reports. Several of these strategies may apply to your community's problem. It is critical that you tailor responses to local circumstances, and that you can justify each response based on reliable analysis. In most cases, an effective strategy will involve implementing several different responses. Law enforcement responses alone are seldom effective in reducing or solving the problem. Do not limit yourself to considering what police can do: give careful consideration to who else in your community shares responsibility for the problem and can help police better respond to it.

Because a drug market can become entrenched fairly quickly, budding drug markets should not be ignored. Early intervention makes good use of scarce police resources since entrenched drug markets are fertile ground for other criminal activity.§

§ During this stage, officers will also assess the resources available to them (personnel, equipment, time, money, etc.) and the political sentiment of the community and government administrators (police, mayoral, legislative, prosecutorial) toward civil, criminal and other remedies.

General Considerations for an Effective Strategy

1. Enlisting property owners' help in closing a drug market. Drug dealing in apartment complexes exacts high costs. Aside from the health costs associated with use and addiction, and the physical risks to the safety of tenants, property managers and dealers themselves, there are considerable financial costs to the property owner. Consider using these costs to engage the property owner in tackling the problem.Most apartment complexes where drug dealing occurs experience many other problems as well, including high tenant turnover and vacancy rates; vandalism or squatting in vacant apartments; increased calls to police; increased police presence on the property; poor reputation of the complex and the property management among neighbors, police and local realtors; lower property values for the complex and for surrounding properties; fear among law-abiding tenants (including fear of retribution); apathy among law-abiding tenants if they perceive the property owner as ignoring or encouraging the market; ceding of common space by lawabiding tenants to those engaged in crime; isolation of lawabiding tenants who stay indoors when dealing (and crimes associated with dealing) are more prevalent; and illicit gun possession by those (sometimes juveniles) seeking to protect themselves against dealers. The presence of drug-dealing tenants in an apartment complex sometimes attracts other criminals as tenants, because the drug dealing can mask their activities or provide them with a ready market for their activities.

In addition, the property owner might incur these typical financial costs:

| $ 500 | Average cost if drug dealer simply stops paying rent for one month |

| $ 50 | Dispossessor warrant |

| $ 25 | Writ of possession |

| $ 250 | Loss of rent due to tenant turnover |

| $ 150 | Labor costs of a painter |

| $ 100 | Paint costs |

| $ 100 | General cleaning of apartment |

| $ 40 | Carpet cleaning |

| $1,215 | Cost to property owner (if there is no damage to the apartment)§ |

§ Officer Tracy Walden, Savannah (Georgia) Police Department, uses these estimates to show owners of apartment complexes where drug dealing is occurring just how significant the cost of one dealer can be to their bottom line. In San Diego, some dealers in apartment complexes file for bankruptcy when faced with eviction, adding six more months to the eviction process (and a loss of six months in unpaid rent). In addition, other tenants sometimes bail out of their leases if drug dealing occurs on a property, increasing the number of vacancies and loss of monthly rent.

2. Enforcing laws and agreements violated by drug dealing in privately owned apartment complexes. When selecting responses, consider which specific laws and agreements are violated by drug dealing in open or closed markets.- Apartment complex rules: sometimes referred to as "house rules" concerning visitors, noise, use of space, etc.

- State laws: narcotics laws (trafficking, possession and intoxication); alcohol laws; loitering and trespassing laws; health codes; child welfare laws, including child endangerment (if a child is in a dealer's apartment); elder abuse laws (if a dealer is taking advantage of an older person and using his or her residence to deal drugs); vandalism laws; harassment laws; nuisance laws; certain asset forfeiture laws.

- Federal laws: drug-free school zone laws (when the market is near a school); federal tax laws; certain asset forfeiture laws; federal (and sometimes state) housing voucher programs providing disadvantaged tenants with apartments in private complexes subject property owners to special conditions.

- Local laws: nuisance laws; alcohol laws; health codes; local building, fire and environmental code violations (especially if dangerous drugs are chemically mixed in an apartment); dog leash violations (if dangerous dogs are used to protect the market); business or zoning laws regarding operation of an illegal business in a residential property.

- Legal conditions: probation and parole conditions prohibiting visiting or mixing with other probationers or parolees, such as often occurs in a drug market.

Using What We Know From Research on Particular Strategies' Effectiveness

Appendix A outlines a wider range of possible responses to drug dealing in apartment complexes than is presented here. Here we discuss only those responses that have been evaluated through research. It will be evident that some of those most used by police have more limited effectiveness than previously thought.

3. Applying intensive police enforcement. Research suggests that intensive police enforcement at drug hot spots, sometimes referred to as "sweeps" or "crackdowns," has an impact on some buyers, particularly those who want to buy only at markets where the risk of arrest is low. However, intensive enforcement alone can have other, perhaps unintended, consequences. These include alienation of lawabiding community members stopped and questioned, and displacement of drug dealing indoors, thus making it more resistant to police interventions. In addition, because intensive police enforcement is by its very nature temporary, the impact is often only short-term and dependent on the resiliency of the market and the buyers.§ Use of this tactic may also give law-abiding tenants and the property owner the unrealistic notion that a drug market is solely a police problem. Some officers have argued that intensive enforcement shows the community that the police care about the problem; however, some of the unintended effects may, in fact, have the opposite result.§§§ In one study in Kansas City, Missouri, the effect of intensive enforcement, including undercover buys, warrant searches and arrests, lasted only two weeks, after which it almost completely disappeared (Sherman and Rogan 1995).

§§ Other approaches involving the property owner and tenants may have significantly longer-term impact, leaving these two groups better equipped to handle similar problems in the future.

4. Arresting dealers and buyers. Arrest is effective if local courts are willing to impose meaningful sentences on dealers and buyers. This often depends on jail and prison overcrowding and on the number of prior convictions of an arrestee. In many cases, the courts allow those arrested for selling drugs to plead to lesser offenses, or release them on bail between arrest and trial or arrest and plea-bargaining. It is estimated that more than 90 percent of filed criminal cases nationwide result in plea-bargaining. Appendix B provides more details about drugs and the criminal justice system.5. Increasing place guardianship. Research suggests that improved place management can block opportunities for certain crimes, such as drug dealing. Ways to increase place guardianship include

- Showing the owner the financial costs of having a drug market on the property

- Engaging the mortgage bank that holds the loan on the property

- Outlining the physical risks to the owner

- Providing training for the landlord

- Engaging tenants or neighbors in information-gathering and market disruption.

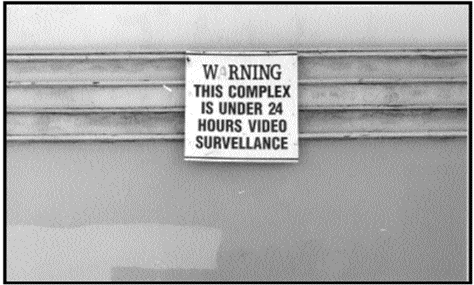

A property owner on a high-risk block affixed this sign to deter potential offenders from the location. Credit: Rana Sampson

§ On several occasions, police agencies in National City and Fontana, California, collaborated with community development or housing agencies to offer "fixer upper" grants to property owners who initially balked at the expense of crime prevention and code compliance improvements.

6. Making physical changes at the property. Limiting access may deter some buyers because it increases their effort in purchasing drugs, but limiting access may also deter the police from entering the property. Limiting escape routes can increase buyers' and dealers' risk of getting caught. As for lighting, dealers may prefer it to be good so that they can better see their customers and the police. Good lighting also reduces the risk that the dealer will get robbed, because it increases the probability of the dealer's identifying the robber.

The owner of this property on a high-risk block off of a main street sends mixed messages to potential dealers looking to set up operations. Next to the “Now Renting” sign is a “No Trespassing” sign, but to its left is the “Residents Only” parking sign, which is lopsided and falling down. The security gate is propped open eliminating its value. Credit: Rana Sampson

7. Sending notification letters to, and meeting with, property owners concerning drug dealing. In a San Diego study, notification letters from police to property owners, coupled with meetings between police and property owners, increased the probability that dealers would be evicted. This also reduced crime at the rental properties as much as 60 percent compared with sites that received no follow-up intervention involving a meeting.5 Police agencies should follow up regularly with those property owners who only reluctantly improve management practices. Police should monitor calls for service at the properties to detect any resurgence of illegal activity, and should document every interaction with the property owners in writing. Notification letters often list consequences for inaction, including abatement, which is described next.

8. Applying civil remedies, including abatement proceedings. Different types of civil remedies can be used to deal with properties sheltering drug markets, including temporary injunctive relief, temporary seizure of premises, permanent seizure of premises, and monetary damages. The district attorney, the police or private citizens can sue in civil court for abatement and/or for financial restitution for the harmed parties.6

9. Evicting drug dealers. The Milwaukee Police Department sought out evicted drug dealers in their new homes to determine if eviction simply displaced dealing to a new area. They found that less than 20 percent of those who were not in jail or prison were still in the drug trade, indicating that displacement levels were low.7

10. Offering drug treatment. Research indicates that there are different ways to offer drug treatment, and that the varying models also vary in effectiveness.

- The information model. Sharing information about drug treatment with users (verbally, through handouts or posters, or by providing phone numbers of referral services) does not appear to be highly effective.§

- The proactive model. Involving drug outreach workers at the site as part of a multiagency response to problems can be effective.8

- The incentive model. Coerced court-based referral, as part of the conditions of probation or sentencing, is effective if coupled with drug-use monitoring and screening.9

Taking Account of Displacement

There is evidence that if displacement occurs, it is not one-for-one. In other words, displacement may be only partial, not enough to cancel the benefits of the countermeasures because the displaced criminal activity lessens and is, as a result, more manageable for the police and community to address.

Displacement indoors. Intensive enforcement alone can displace an open market indoors. Driving a market indoors negatively impacts it, decreasing its customer base because it must rely on word of mouth for advertisement, rather than visual cues. Also, an indoor market is less convenient to buyers (they must park, not just stop momentarily), and buyers may feel less safe, as they now have to enter dealers' homes. However, residents of an apartment complex may not find this a complete solution. Property management must improve to rid the complex of the market.

Displacement nearby. If property management becomes effective, an apartment-complex drug market must close down or move. A review of the displacement literature suggests that there may be ways to minimize nearby displacement.

- Open-market dealers have what is referred to as "high place attachment." They rely on the natural and established routine of foot and car traffic to supply a high volume of buyers. It is high risk for dealers to set up shop in unfamiliar territory; doing so can lead to inter-turf drug warfare, so nearby complexes or other nearby areas with low levels of property guardianship are most at risk for displacement.

- Displacement nearby should be expected since it allows the market to keep most of its customers. Developing a thorough understanding of the reasons the drug market succeeded in the apartment complex can shed light on the conditions that must be changed nearby, especially in nearby complexes, to avert potential displacement.§

§ For a more detailed discussion of displacement and drug markets, see Jacobson (1999) [Full text] [Briefing notes].

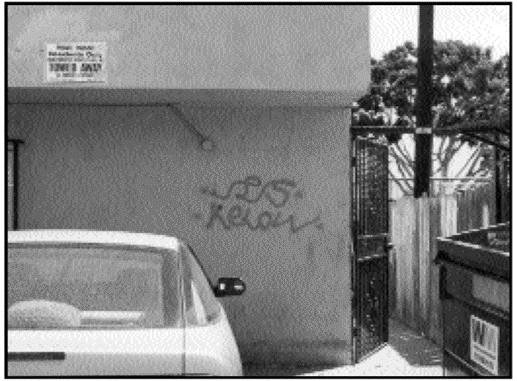

This apartment complex is at high risk for dealing. It is on a block that has had drug markets, is off of an arterial street, backs onto an alley providing multiple entries and exits, is tagged “Kelow,” (probably purposefully misspelled), its alley-side security gate is propped open, and the dumpster is propped open offering an easy hiding place for stash. While a “Residents Only” parking sign is visible, the owner must do more to prevent nearby markets from displacing to this complex. Credit: Rana Sampson

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Drug Dealing in Privately Owned Apartment Complexes

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

- To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

- Your E-mail *

Copy me

- Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.