The Problem of Graffiti

This guide addresses effective responses to the problem of graffiti—the wide range of markings, etchings and paintings that deface public or private property.† In recent decades, graffiti has become an extensive problem, spreading from the largest cities to other locales. Despite the common association of graffiti with gangs, graffiti is widely found in jurisdictions of all sizes, and graffiti offenders are by no means limited to gangs.

† Although graffiti is also found within public or private property (such as in schools), this guide primarily addresses graffiti in places open to public view.

Because of its rising prevalence in many areas—and the high costs typically associated with cleanup and prevention—graffiti is often viewed as a persistent, if not an intractable, problem. Few graffiti offenders are apprehended, and some change their methods and locations in response to possible apprehension and cleanups.

As with most forms of vandalism, graffiti is not routinely reported to police. Many people think that graffiti is not a police or "real crime" problem, or that the police can do little about it. Because graffiti is not routinely reported to police or other agencies, its true scope is unknown. But graffiti has become a major concern, and the mass media, including movies and websites glamorizing or promoting graffiti as an acceptable form of urban street art, have contributed to its spread.

Although graffiti is a common problem, its intensity varies substantially from place to place. While a single incident of graffiti does not seem serious, graffiti has a serious cumulative effect; its initial appearance in a location appears to attract more graffiti. Local graffiti patterns appear to emerge over time, thus graffiti takes distinctive forms, is found in different locations, and may be associated with varying motives of graffiti offenders. These varying attributes offer important clues to the control and prevention of graffiti.

For many people, graffiti's presence suggests the government's failure to protect citizens and control lawbreakers. There are huge public costs associated with graffiti: an estimated $12 billion a year is spent cleaning up graffiti in the United States. Graffiti contributes to lost revenue associated with reduced ridership on transit systems, reduced retail sales and declines in property value. In addition, graffiti generates the perception of blight and heightens fear of gang activity.

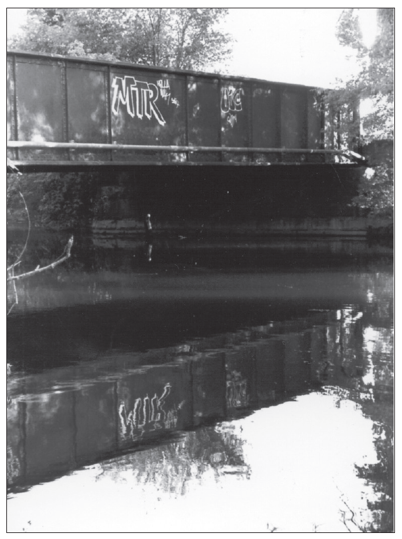

Graffiti offenders risk injury by placing graffiti on places such as this railroad bridge spanning a river. Credit: Kip Kellogg

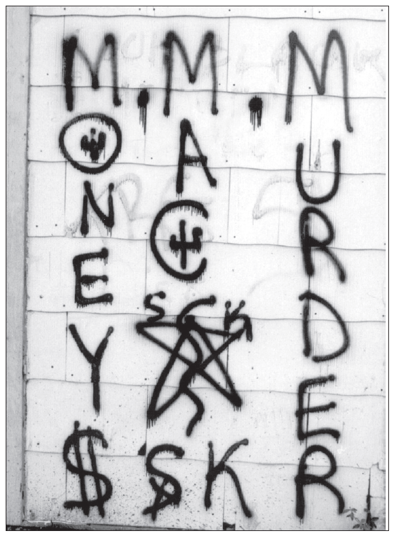

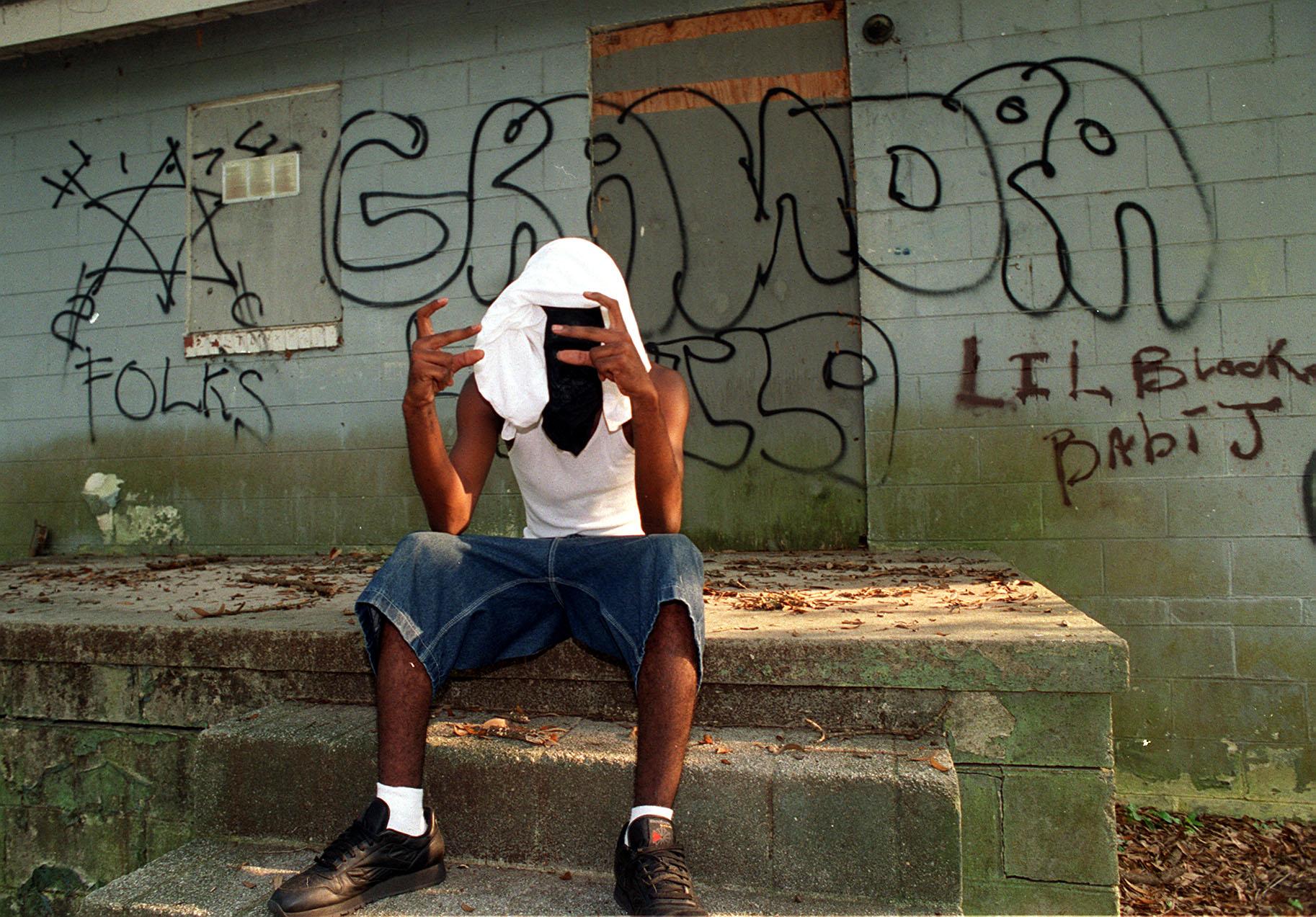

Gang graffiti marks territory and conveys threats. Credit: Bob Morris

Related Problems

Graffiti is not an isolated problem. It is often related to other crime and disorder problems, including:

- Public disorder, such as littering, public urination and loitering

- Shoplifting of materials needed for graffiti, such as paint and markers1

- Gangs and gang violence, as gang graffiti conveys threats and identifies turf boundaries

- Property destruction, such as broken windows or slashed bus or train seats.

Factors Contributing to Graffiti

Understanding the factors that contribute to your problem will help you frame your own local analysis questions, determine good effectiveness measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses.

Types of Graffiti

There are different types of graffiti. The major types include:

- Gang graffiti, often used by gangs to mark turf or convey threats of violence, and sometimes copycat graffiti, which mimics gang graffiti

- Tagger graffiti, ranging from high-volume simple hits to complex street art

- Conventional graffiti, often isolated or spontaneous acts of "youthful exuberance," but sometimes malicious or vindictive

- Ideological graffiti, such as political or hate graffiti, which conveys political messages or racial, religious or ethnic slurs.

In areas where graffiti is prevalent, gang and tagger graffiti are the most common types found. While other forms of graffiti may be troublesome, they typically are not as widespread. The proportion of graffiti attributable to differing motives varies widely from one jurisdiction to another.† The major types of graffiti are discussed later.

† A count in a San Diego area with a lot of graffiti showed that about 50 percent was gang graffiti; 40 percent, tagger graffiti; and 10 percent, nongroup graffiti (San Diego Police Department 2000). In nearby Chula Vista, Calif., only 19 percent of graffiti was gang-related (Chula Vista Police Department 1999). Although the counting methods likely differ, these proportions suggest how the breakdown of types of graffiti varies from one jurisdiction to another.

Common Targets and Locations of Graffiti

Graffiti typically is placed on public property, or private property adjacent to public space. It is commonly found in transportation systems—on inner and outer sides of trains, subways and buses, and in transit stations and shelters. It is also commonly found on vehicles; walls facing streets; street, freeway and traffic signs; statues and monuments; and bridges. In addition, it appears on vending machines, park benches, utility poles, utility boxes, billboards, trees, streets, sidewalks, parking garages, schools, business and residence walls, garages, fences, and sheds. In short, graffiti appears almost any place open to public view.

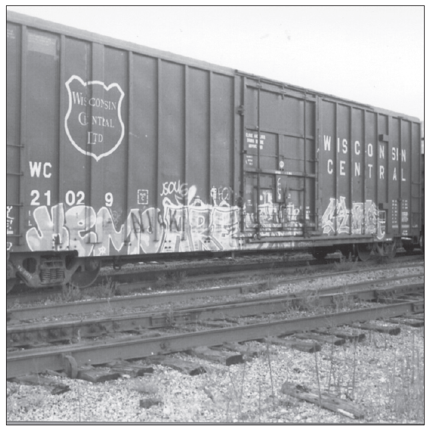

Graffiti is commonly found in transportation systems, such as on the side of this railroad car. Credit: Kip Kellogg

Graffiti tends to recur in some locations. In fact, areas where graffiti has been painted over—especially with contrasting colors—may be a magnet to be revandalized.† Some offenders are highly tenacious—conducting a psychological battle with authorities or owners for their claim over an area or specific location. Such tenacity appears to be related to an escalating defiance of authority.

† Most sources suggest that paint-over colors should closely match, rather than contrast with, the base. Contrasting paint-overs are presumed to attract or challenge graffiti offenders to repaint their graffiti; the painted-over area provides a canvass to frame the new graffiti.

Graffiti locations are often characterized by the absence of anyone with direct responsibility for the area. This includes public areas, schools, vacant buildings,2 and buildings with absentee landlords. Offenders also target locations with poor lighting and little oversight by police or security personnel.

Some targets and locations appear particularly vulnerable to graffiti:

- Easy-to-reach targets, such as signs

- Particularly hard-to-reach locations, such as freeway overpasses

- Highly visible locations, such as building walls

- Locations where a wall or fence is the primary security, and where there are few windows, employees or passersby

- Locations where oversight is cyclical during the day or week, or where people are intimidated by graffiti offenders

- Mobile targets, such as trains or buses, which generate wide exposure for the graffiti

- Places where gang members congregate—taverns, bowling alleys, convenience store parking lots, and residential developments with many children or youth.

In addition, two types of surfaces attract graffiti:

- Light-colored surfaces. Dark surfaces do not generally attract as much graffiti, but can be marred with light-colored paint.

- Large and plain surfaces. Surfaces without windows or doors may be appealing for large-scale projects. Smooth surfaces especially attract offenders who use felt-tip markers.

Motives of Offenders

While making graffiti does not offer material reward to offenders, contrary to public opinion, it does have meaning. Rather than being a senseless destruction of property, graffiti fulfills certain psychological needs, including providing excitement and action, a sense of control and an element of risk. The different types of graffiti are associated with different motives, although these drives may overlap.† Distinguishing between types of graffiti and associated motives is a critical step for developing an effective response.

† The description of types of graffiti and motives of graffiti offenders draws from broader typologies and motives associated with vandalism. See, for example, Coffield (1991) and Cohen (1973).

Historically, much conventional graffiti has represented a youthful "rite of passage"—part of a phase of experimental behavior. Such graffiti is usually spontaneous and not malicious in nature; indeed, spontaneous graffiti has often been characterized as play, adventure or exuberance. Spontaneous graffiti may reflect local traditions and appear on "fair targets" such as abandoned buildings or schools. Communities have often tolerated such graffiti (See Table 1).

The motives for some types of conventional graffiti may include anger and hostility toward society, and the vandalism thus fulfills some personal psychological need.3 The graffiti may arise from boredom, despair, resentment, failure, and/or frustration, in which case it may be vindictive or malicious.

A related type of graffiti is ideological. Ideological graffiti expresses hostility or a grievance—often quite explicitly. Such graffiti is usually easily identified by its content, reflecting a political, religious, ethnic, or other bias. Offenders may strategically target certain locations to further the message.

In contrast to conventional and ideological graffiti, the primary motive for gang graffiti is tactical; the graffiti serves as a public form of communication—to mark turf, convey threats or boast of achievements.4

Some tagger graffiti may involve creative expression, providing a source of great pride in the creation of complex works of art. Most taggers seek notoriety and recognition of their graffiti—they attach status to having their work seen. Thus, prolonged visibility due to the sheer volume, scale and complexity of the graffiti,† and placement of the graffiti in hard-to-reach places‡ or in transit systems, enhance the vandal's satisfaction.5 Because recognition is important, the tagger tends to express the same motif—the graffiti's style and content are replicated over and over again, becoming the tagger's unique signature.

† This includes complex, artistic graffiti known as masterpieces.

‡ Taggers in California used climbing equipment to tag freeway overpasses, knowing their tags would be highly visible for extended periods, until the road was shut down for paint-overs (Beatty 1990). Hardto-reach places also provide an element of danger of apprehension or physical risk, contributing to the vandal's reputation.

Table 1: Types of Graffiti and Associated Motives

| Type of Graffiti | Features | Motives |

| Gang¶ |

|

|

| Common Tagger§ |

|

|

| Artistic Tagger |

|

|

| Conventional Graffiti: Spontaneous |

|

|

| Conventional Graffiti: Malicious or Vindictive |

|

|

| Ideological |

|

|

¶ Copycat graffiti looks like gang graffiti, and may be the work of gang wanna-bes or youths seeking excitement.

† Offenders commonly use numbers as code in gang graffiti. A number may represent the corresponding position in the alphabet (e.g., 13 = M, for the Mexican Mafia), or represent a penal or police radio code.

‡ Stylized alphabets include bubble letters, block letters, backwards letters, and Old English script.

§ Tagbangers, a derivative of tagging crews and gangs, are characterized by competition with other crews. Thus crossed-out tags are features of their graffiti.

± The single-line writing of a name is usually known as a tag, while slightly more complex tags, including those with two colors or bubble letters, are known as throw-ups.

Characteristics and Patterns of Graffiti Offenders

Graffiti offenders are typically young and male. In one study, most offenders were ages 15 to 23; many of the offenders were students. Offenders may typically be male, inner-city blacks and Latinos, but female, as well as white and Asian, participation is growing.7 The profile clearly does not apply in some places where the population is predominantly white. Tagging is not restricted by class lines.

In Sydney, Australia, graffiti offenders, while mostly boys, include girls; offenders are typically ages 13 to 17.8 In San Diego, all the taggers identified within a two-mile area were male, and 72 percent were 16 or younger.9

Graffiti offenders typically operate in groups, with perhaps 15 to 20 percent operating alone.10 In addition to the varying motives for differing types of graffiti, peer pressure, boredom, lack of supervision, lack of activities, low academic achievement, and youth unemployment contribute to participation in graffiti.

Graffiti offenders often use spray paint, although they may also produce graffiti with large markers or by etching, the latter especially on glass surfaces.† Spray paint is widely available, easily concealed, easily and quickly used on a variety of surfaces, available in different colors with different nozzles to change line widths—these factors make spray paint suitable for a range of offenders.‡

† Other tools for graffiti include shoe polish, rocks, razors, glass cutters, and glass etching fluid. Glass etching fluids include acids, such as Etch Bath and Armour Etch, developed as hobby products for decorating glass. Vandals squirt or rub the acids onto glass.

‡ Vandals may adapt or modify tools and practices to cleaning methods. In New York City, when transit system personnel used paint solvents to remove graffiti, offenders adapted by spraying a surface with epoxy, writing their graffiti and then coating the surface with shellac, which proved very difficult to remove.

The making of graffiti is characterized by anonymity—hence relative safety from detection and apprehension. Most offenders work quickly, when few people are around. Graffiti predominantly occurs late on weekend nights, though there is little systematic evidence about this. In British transit studies, graffiti incidents typically occurred in off-peak or non-rush hours.11 In Bridgeport, Conn., graffiti incidents were concentrated from 5:00 p.m. to 4:00 a.m. Thursdays through Sundays.12 A San Diego study showed that routes leading away from schools were hit more frequently, suggesting a concentration in after-school hours Monday through Friday. Offenders tagged school walls daily.13

There is widespread concern that participation in graffiti may be an initial or gateway offense from which offenders may graduate to more sophisticated or harmful crimes. Graffiti is sometimes associated with truancy, and can involve drug and/or alcohol use. Graffiti offenders who operate as members of gangs or crews may also engage in fighting.

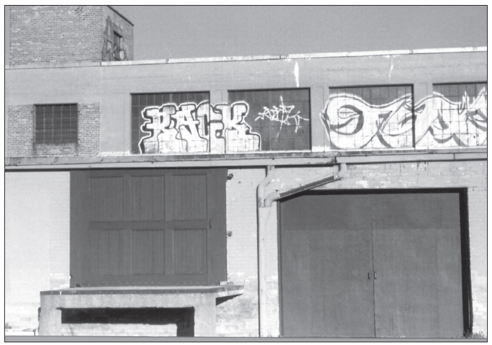

Graffiti often appears in hard-to-reach yet highly visible locations, such as on the upper-story windows of this warehouse. Credit: Kip Kellogg

Young male gang members may engage in a substantial amount of graffiti. Credit: Bob Morris

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Graffiti

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

- To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

- Your E-mail *

Copy me

- Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.