Setting a Realistic Timetable

Once you have selected responses, you should pay careful attention to how long the response implementation will take. There are a number of reasons for this:

- Stakeholders and intervention recipients will expect the implementation to be completed within a specified time.

- Failure to meet the deadline may reflect poorly on the implementing team and on the organization as a whole.

- There is an opportunity cost associated with extended implementation periods in that additional time spent on a response will detract from other work that the implementing team could be undertaking.

- In some cases, there may be a very real financial cost, especially if delays mean that contracted staff or hired equipment needs to be used for a longer period.

Most of us pay little attention to the timetables required for a response, and calculate these in one of two ways. We either pick a time off the top of our head, based on a rough calculation of how long the most salient tasks will take, or we think of a deadline first and then fit the tasks into the available time. From a planning perspective, neither is sufficient, as both allow for the possibility of significant time overruns.

A preferred approach to developing a realistic timetable is to produce a Gantt chart using the following “key stage” approach:

- Identify all of the individual tasks involved in the intervention.

- Group these tasks into “key stages,” based on activities that appear to relate to each other and that, ideally, can be assigned to a single person. While you may have a hundred individual tasks, these may be grouped into, say, a dozen key stages.

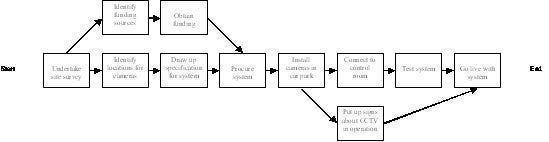

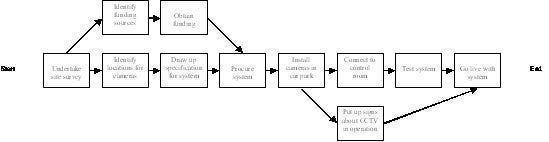

- Order the stages into a logical sequence showing dependencies between key stages. Look for opportunities for running key stages in parallel, as the more that are run in parallel, the shorter the overall project time. This should result in a “project logic diagram.” Figure 1 provides a project logic diagram for installing a CCTV system in a parking ramp. Note that there are two points at which key stages are run in parallel. In producing the project logic diagram, you should take into account the following rules:

- Time flows from left to right.

- There is no timescale attached at this stage.

- Place a start box on the left of the sheet.

- Place a finish box at the end of the sheet.

- There should be one box for each key stage.

- Start each key stage with a verb.

- Do not add durations at this point.

- Place boxes in order of dependency, debating each one.

- Validate dependencies by working through the process.

- Do not take people doing the work into account.

- Do not add in responsibilities at this stage.

- Draw in the dependency links with straight arrows.

- Avoid arrows that cross.

- Next, work out how long the tasks associated with the key stage take to complete. Much of this will be estimation, but the principle here is that the sum total of lots of small estimates associated with tasks will be more accurate than attempting to estimate the overall time taken to complete a project. Remember that some of the tasks may be completed in parallel, which will obviously save time in completing the key stage. You should now have an estimate of the time it will take to complete each key stage.

- The final stage is to work out the “critical path.” The project logic diagram shown in Figure 1 has three paths that can be followed between the start and finish. One goes straight through the middle, the second passes through “identify funding sources” and “obtain funding,” and the third passes through “put up signs about CCTV in operation.” The critical path is the one that takes the longest to pass from start to finish. This represents the shortest possible time in which the project can be completed, and will allow you to calculate the deadline by which you can complete the response.

- Working this way, you may find that the response takes longer than you had expected. However, having this kind of information allows you to make decisions about how to undertake the response. You may find that you can speed up some key stages by providing more resources to complete it (for example, two people may complete the job faster than one), or by cutting back on the quality on some aspects of the work. Ultimately, you might decide that a response is likely to take too long to complete, and that you should select an alternative response.

The point of undertaking this exercise at the planning stage is that, by taking a little time to work out how long it is likely to take, you can plan how to complete the project more quickly or to change directions before incurring implementation expenses and having to make changes while the response is in progress.

Analyzing Risks

At the planning stage, you should also consider the implementation risks faced in the response. In identifying risks, you should pay particular attention to those that are most closely related to a response (for example, one could highlight and plan for the risk of being hit by a meteorite, but the chances of that happening are slim), and about which one can do something. You should consider risks in terms of both the likelihood of occurrence and the impact they will have on the response, using the risk matrix shown in Figure 2. Pay particular attention to those where the likelihood and risk of occurrence are highest. Risks can also be divided into two kinds-those associated with implementation failure, and those associated with theory failure (for example, the mechanism of change does not operate as expected).

| Impact on Project |

| Likelihood of Occurrence |

| |

Low |

Medium |

High |

| Low |

Low risk |

Medium risk |

High risk |

| Medium |

Low risk |

High risk |

Immediate action |

| High |

Medium risk |

High risk |

Immediate action |

Figure 2. Risk Matrix.

The table below provides an example of a risk analysis undertaken in relation to a project to install a CCTV system. This shows the risks that have been identified, their likelihood of occurrence, their impact, and proposed actions to address them.

Table. Example of a Risk Analysis

| Risk |

Likelihood of Risk |

Impact of Risk |

Action to be Taken |

| The CCTV system does not provide adequate coverage due to a limited number of cameras. |

Low |

High |

In drawing up the specifications, ensure that sufficient camera sites are identified. |

| The camera pictures’ resolution is insufficient to identify people. |

Low |

Medium |

Test the cameras’ resolution before making a final decision on the system. |

| It proves difficult to maintain the system in the future. |

Medium |

Medium |

Produce a plan for how the system will be maintained and for its associated costs. |

Once you have identified risks, you can take a number of approaches to deal with them, including the following:

- Prevention: You may design a response to prevent a certain risk from occurring, or to prevent that risk from having an adverse impact on the response.

- Reduction: If you cannot prevent a risk, then it may be possible to reduce the extent to which it occurs, or to limit the impact when it does.

- Transference: Here the risk is transferred to a third party. For example, an insurance policy is an example of risk transference.

- Contingency: This involves planning activities that come into action if a particular risk occurs, with a view to overcoming the problems faced.

- Acceptance: Here you simply continue in the knowledge that there are risks associated with the response, and deal with them as and when they arise.

Producing an Action Plan

As part of the response planning stage, you should draw up an action plan that details what is to be undertaken, how it is to be undertaken, who is to be involved, and over what time periods it will be undertaken. The list below provides an outline of what might be included in this action plan:

- response title;

- response goals and objectives;

- staff involved in delivering the response;

- start date;

- end date;

- description of interventions to be undertaken, and how they will be implemented;

- outstanding issues that need to be addressed before implementation can start;

- response outputs;

- risk assessment and contingency planning associated with each intervention;

- timetable for each intervention, including planned milestones;

- overall response costs, broken down by intervention; and

- projected response cash flow.

The action plan provides an opportunity to share your ideas about how the response will be undertaken, and to identify changes you should make before the implementation process starts. This is an extremely important part of the process, as by sharing the plan, you can obtain “buy-in” from stakeholders, as well as take on board the perspectives of others who may help to shape a more effective response.