Export of Stolen Vehicles Across Land Borders

Guide No. 63 (2012)

The Problem of Export of Stolen Vehicles Across Land Borders

Each year a large number of cars and trucks are stolen for export in regions of the United States bordering Mexico. Most of these vehicles are simply driven across the border where they generally remain. By contrast, few stolen vehicles are reportedly exported across the border with Canada.† This guide is therefore mostly concerned with the problem of vehicles stolen for export to Mexico, though it should also be useful to police dealing with the problems of exporting stolen vehicles across land borders elsewhere in the world.‡

† Analyses of the nationwide distribution of auto theft, discussed in the "Extent of the Problem" section of this guide, show little evidence of concentrations in border areas with Canada. This suggests there is little demand in that country for stolen U.S. vehicles.

‡ For example, many cars stolen in South Africa are driven across borders to other African countries. The demise of the Soviet system resulted in a large number of cars being stolen in Western Europe and exported across land borders to Russia and other Eastern European countries. The emerging market economies in those countries created a demand for cars that domestic producers could not meet, and criminal entrepreneurs moved in to fill the gap.

This guide is primarily intended to help local police deal with theft for export, though it might also be of value to county or state agencies. It summarizes the factors that put local jurisdictions at risk of theft for export, and provides a method of estimating the size of their problem. It identifies information that police should collect when engaged in a problem-oriented project to reduce theft for export. Finally, it provides details on methods that have been developed to deal effectively with this problem.

What This Guide Does and Does Not Cover

This guide describes the problem of export of stolen vehicles across land borders and the factors that increase its risks. It includes a series of questions to help you analyze your local problem and reviews responses to the problem and what is known about these responses from evaluative research and police practice.Export of stolen vehicles across land borders is but one aspect of the larger set of problems related to vehicle theft and the set of problems related to border crossings. This guide is limited to addressing the particular harms created by the export of stolen vehicles across land borders. Related problems not directly addressed in this guide, each of which requires separate analysis, include:

Stolen Vehicle Problems

- Export of stolen vehicles via seaports or airports

- Theft of and from vehicles in parking facilities

- Theft of and from vehicles parked on streets

- Theft of vehicles from rental agencies and dealerships

- Insurance fraud related to auto theft

- Carjacking

- Operation of chop shops

Border Crossing Problems

- Illegal border crossing

- Robbery and assault of border crossers

- Drug trafficking across borders

- Human trafficking

Some of these related problems are covered in other guides in this series. An up-to-date list of current and future guides is at www.popcenter.org.

The Extent of the Problem

There are no reliable statistics for the number of stolen vehicles that are exported across land borders because police-recorded crime subsumes these vehicles under the larger category of unrecovered vehicle thefts. Although the Uniform Crime Reports do not record the number of unrecovered stolen vehicles, in 2009 the value of these vehicles was reportedly $1.96 billion, with an average loss per theft of $6,505. A simple calculation of these numbers yields a figure of about 301,300 unrecovered vehicle thefts in that year.

Apart from vehicles stolen for export, these unrecovered thefts include vehicles that are:

- Kept by the thief

- Given a new identity and sold on the domestic market

- "Chopped" for sale of their parts

- Taken by joyriders and "torched" (i.e., destroyed by fire) or abandoned and never restored to their owners

- Arranged to be stolen so the owner can fraudulently collect the insurance money.

The number of unrecovered vehicles falling into these categories is not known. It is also not known how many vehicles stolen for export are driven across land borders and how many are exported by sea.

Despite the lack of hard numbers, there is much evidence that theft of vehicles for export across land borders—in particular the border with Mexico—is a substantial problem. Several research studies have found that the number of unrecovered thefts is higher, sometimes much higher, in regions of the country that are closer to the border. No known reason other than theft for export to Mexico can account for this disproportion of unrecovered thefts, which is documented in the following studies:

1. Aldridge (2007) reports that in 2005 about one third of all recorded vehicle thefts in the United States (413,864 out of 1,244,525) occurred in the four states bordering Mexico (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas). Based on the number of vehicles registered in these four states, which according to the U.S. Census Bureau1 is only 23 percent (57,634,000) of all vehicles registered in the United States, this proportion is substantially higher than expected. Aldridge also reports that California's vehicle theft rate was more than double the national average, but the vehicle theft rate in just the southern portion of San Diego County, which borders Mexico, was four times the national average. The San Diego Police Department Southern Division (directly across the Mexican border) reported a rate of 17.45 auto thefts per 1,000 inhabitants. The rest of San Diego County reported theft rates as low as 2.72 per 1,000 inhabitants.2

2. The National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB) publishes data on vehicle theft rates in Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA). These are calculated by dividing the number of vehicle thefts in the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database by the U.S. Census Bureau's population estimates. NICB reports show evidence consistent with theft for export: eight of the top 10 ranked MSAs in 2010 were in California, of which the majority were in southern or central California, close to the border with Mexico.

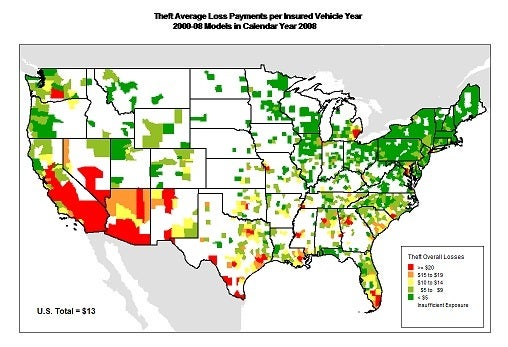

3. A report produced in 2009 by the Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI), a nonprofit research organization funded by automobile insurance companies, concluded that (a) theft losses in the Mexican border area have increased greatly over the last 8 years;† (b) these losses are generally concentrated in southern portions of Texas and Arizona; and (c) they are skewed more toward border areas when compared to overall vehicle thefts, indicating a prevalence of unrecovered thefts (see Figure 1). According to this report, "Six of the 10 metropolitan statistical areas with the worst (highest) theft losses are along the border with Mexico, and one is near the border. The other three with the highest theft losses are port cities." The report's many maps clearly demonstrate that vehicle thefts are prevalent in counties near borders and ports. In addition, the report concludes that this pattern of concentration has increased in recent years, which suggests that theft for export is a growing problem.‡

† This is consistent with other evidence reviewed by Cherbonneau and Wright (2009) that shows a growing concentration of vehicle thefts in western states, where theft rates have increased by 33 percent since 1999. During the same time period, theft rates in all other regions of the country have declined by 37 percent.

‡ Some law enforcement authorities believe this growth is fueled by an emerging "cars for cocaine" trafficking problem. A Division of Motor Vehicles office opened at the Port of Miami in Florida to help deal with this suspected problem (Leen 1985).

Figure 1: Theft Average Loss Payments per Insured Vehicle Year 2000 - 09 Models in Calendar Year 2009

Source: Highway Loss Data Institute (2009)

4. Block et al. (2011) conducted a geographic analysis to estimate the size of the theft for export problem. They found that vehicle thefts were overrepresented in high-traffic border areas when compared with levels of other index crimes. For example, three of the top five counties for vehicle theft shared a border with Mexico (Pima and Santa Cruz, Arizona and San Diego, California). At the state level, California and Arizona had about 110,000 more vehicle thefts than would be predicted by levels of other index offenses.3

Not all of these 110,000 stolen vehicles would have been exported to Mexico. For example, some of the vehicles stolen in California might have been shipped overseas. This figure also does not include thefts for export to Mexico from other states. However, the figure is broadly consistent with the estimate made for many years by the NICB that 30–35 percent of unrecovered stolen vehicles were exported† and it provides the best estimate available of the extent of the problem.

† The NICB no longer publishes these estimates because of untested assumptions in producing them (Clarke and Brown 2003).

Federal and other agencies' concerted efforts in dealing with the problem of vehicles stolen for export to Mexico provide further evidence of its scale and importance. For example, the United States developed a model bilateral agreement for the repatriation of stolen vehicles (see United Nations 1997) and signed it with several Latin American countries. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) opened its stolen vehicle database to other countries (Davis 1999). The NICB (which is supported by the American insurance industry) has stationed officials in Mexico and other South American countries to assist in the process of repatriating vehicles. Various law enforcement agencies in border regions have formed task forces to deal with auto theft, including the California Highway Patrol, El Paso County Sheriff's Office, and the Texas Department of Public Safety. (See the "Reponses to the Problem of Vehicles Stolen for Export Across Land Borders" section of this guide.)Though difficult to identify, measure, and analyze, there is little doubt that the problem of vehicles stolen for export across the border with Mexico is significant in terms of the numbers of vehicles stolen and the total dollars lost. The problem affects many regions of the country and cannot be ignored.

The Nature of the Problem

Because of the lack of data concerning the theft for export problem, there are only a few research studies on the nature of the problem. However, research does provide some information on who commits the thefts, how the vehicles are stolen and transferred across the border, and which models are most at risk. Following is a summary of this information.

Who Commits the Thefts

Research suggests that juveniles often commit vehicle thefts.† One study found that large organized theft rings, "frontera-rings," are involved in the business of transporting stolen cars from the United States to Mexico,4 but they rely upon Mexican juveniles—who are brought to border cities—to steal the cars.5 Other less sophisticated theft rings also rely on adolescents for "cross-border stealing."6 In some cases, juvenile offenders operate largely independently7 and might "steal a car in the afternoon and sell it that same evening in Mexico."8

† This may be different from theft for export in other parts of the world. INTERPOL (1999) reports that "German authorities, for example, found that stealing expensive German cars was common among Russian organized crime groups. Some scholars argue that in Russia, for example, it is unlikely for many individuals to have the 'necessary expertise to steal cars, the skills to falsify documents, the connections to smuggle them across borders, falsify documents in Russia that allows registration of these cars, and also find buyers for them.'"

Though there is little firm evidence of this, it's believed that both legal and illegal immigrants are involved in exporting stolen vehicles, as they may have the necessary contacts, resources, and knowledge of the market for vehicles. They are also known to be involved in many other forms of transnational crime, such as human smuggling and drug trafficking.

There is anecdotal evidence that some seasonal workers from Mexico steal cars to take back home (just as seasonal workers in Sweden are said to do9). They might subsequently return to the United States in the same vehicles, as there are occasional reports of cars known to be stolen for export subsequently being stopped by police in this country.

How the Vehicles Are Stolen

One careful study shows that border car thieves often cruise large parking lots, such as those used by city workers, commuters, or customers of stores such as Home Depot, looking for suitable cars to steal. They are secure in the knowledge that owners are likely to be away from their vehicles for several hours, which is long enough to get a vehicle across the border before its theft is discovered.10

Thieves also might pay a small fee to car park attendants and security guards, who can provide valuable information about the location of particular models and may help in other small ways.11

How the Stolen Vehicles Are Transported Across the Border

Although some stolen vehicles are loaded onto trucks, most are simply driven across the border.† Thieves who steal cars near Mexico usually drive them across the border without changing their identities. If they cross the border before the car is reported stolen, it is highly likely they will avoid detection.

† Moving stolen vehicles from South Africa to Zimbabwe often involves driving the vehicles to the border area where new drivers, who have better knowledge of border procedures and contacts in the destination country, take the vehicles through the border. In other cases, vehicles are driven across borders on dates and at times when border officials who are known to accept bribes are on duty at the border post (Irish 2005).

Which Vehicle Models Are at Risk

Certain vehicle models are at a higher risk of being stolen for export. Early studies found that these are models that "blend in" because they are also manufactured or sold legitimately in Mexico.12

A more recent study in Chula Vista, California, a city close to the Mexican border, found that five models accounted for 43 percent of the vehicles stolen. Three of these models were small pick-up trucks manufactured by Toyota, Nissan, and Ford.13

In 2009, five of the top 10 stolen vehicles in Arizona were pick-up trucks, compared with two out of 10 nationwide. Pick-up trucks and large sports utility vehicles (SUV) are sought after by Mexican criminal gangs, who use them as "load vehicles" to transport either illegal immigrants or illegal drugs from Mexico into the United States.14

Factors Contributing to the Problem

Poor Vehicle Security

The routine installation of central locking systems and ignition transponders in recent years has greatly improved the security of new vehicles and has contributed to a large decline in vehicle theft, especially of new cars.15 This improved security also may have reduced thefts for export across land borders, if, as it seems, many of the thefts are committed by juveniles; however, there are no reliable statistics to support this. On the other hand, when the security of new cars is improved, thieves will displace their attention to older models.16 Because there are still many older vehicles available to steal, it may be a few years before improved vehicle security reduces theft for export to Mexico.†

† In explaining the presence of old Toyotas on their list of the five most stolen vehicles in Chula Vista, California, Plouffe and Sampson (2004) learned from interviewing thieves who admitted taking cars into Mexico that: "Some targeted older Toyotas, as any old Toyota ignition key opened and started the vehicle, reducing the effort involved in stealing these vehicles. This last finding came as a surprise to auto theft detectives, who had believed that auto thieves used shaved keys. Offenders picking old Toyotas didn't even have to make the effort to shave an old key."

Proximity to the Border with Mexico

In addition to the studies described above, following is more evidence that supports the strong correlation between auto theft rates and proximity to the Mexican border:

Difficulties of Checking Vehicles Crossing into Mexico

Many difficulties stand in the way of checking vehicles that cross the border into Mexico from the United States:

- A vast number of vehicles use border crossings into Mexico every day. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, more than 70 million vehicles, carrying twice that number of passengers, crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in 2009.21 Looking for stolen cars among this vast amount of legal traffic is like searching for the proverbial needle in the haystack.

- A substantial legal trade of used cars exists between the United States and Mexico. A large number of used cars are legally traded between the United States and Mexico. Some criminals involved in trafficking stolen cars hide behind this trade, masking their activities as legitimate business. In fact, the top two items exported from the United States to Mexico in 2009 were motor vehicle parts and motor vehicles, respectively.22

- U.S. border controls are focused on arrivals, not departures. Customs officers are responsible for levying duties on certain goods entering the country and keeping prohibited goods out. In the United States, this focus on arrivals has become more pronounced as fears of terrorism have increased.23

- Language barriers make border control difficult.Language barriers make it difficult for Mexican officials to check registration and ownership documents and to detect forged or altered papers.

- Vehicle theft is not a high priority for law enforcement.24 Law enforcement action to reduce the export of stolen vehicles is eclipsed by the need to tackle other forms of organized crime (e.g., importing drugs and human trafficking).25 Developing countries, such as Mexico, are faced with many crime problems more serious than the import of stolen cars and cannot be expected to give this high priority.

An example of the daily vehicle congestion at a border crossing between the United States and Mexico.

Strong Demand in Mexico for Vehicles Stolen in the United States

The export of stolen vehicles relies on a ready supply of attractive vehicles in a developed country, the demand for these vehicles in another, less developed country, and a ready means of transporting them from origin to destination.26 These three conditions help explain the problem of vehicles stolen for export to Mexico. They also help explain the increase in car theft in Europe following the fall of the "Iron Curtain" in 1989, which brought the "wealthy half of the continent, where consumer goods are available in unlimited quantities, into close contact with the poor half," where these commodities are in high demand but not readily available.27 Some estimates suggest that about 20–35 percent of the newer, expensive cars in Russia were stolen in Western Europe.28

Mexican Legislation Governing Import of Vehicles

To protect the national automobile industry in Mexico, the import of vehicles less than 4-years-old is prohibited. Older vehicles can be brought into the 20-kilometer border zone under permit after a 15 percent duty is paid.29 Stolen vehicles exported to Mexico that do not meet these requirements are labeled as contraband rather than as stolen property. These cars are then confiscated and used by police and officials, rather than considered stolen and returned to the United States.30

Corruption

Disposing of a stolen vehicle in the destination country usually meets few challenges.† In Russia, for example, the false documents used to bring the car into the country from Western Europe are destroyed and a new set of illegal documents are produced. This is usually accomplished with the help of corrupt law enforcement and other officials.31

† In South Africa, corruption (and intimidation) of officials in vehicle registration offices is one method of obtaining a new identity for stolen vehicles, many of which are exported to neighboring countries (Ndhlovu 2002).

In Mexico, once stolen cars are in the black market for sale, a bribe to officials can often deal with the threat of confiscation.32 Corruption exists not only inside Mexico, but also on the U.S.-Mexico border, where there is believed to be a "general understanding" between Mexican Customs officials and those who transport stolen vehicles.33

Insurance Fraud

In Western Europe, insurance fraud is "one of the driving forces behind" vehicle theft for export.34 In some instances, owners of luxury vehicles sell their cars to Eastern European criminals for a fraction of their value, do not report the 'thefts' to the authorities until the cars have crossed the international border, and then collect money from their insurance company. In such cases, the owners collect money both from the 'thieves' and the insurance company. In other instances, 'thieves' do not pay the owner, and he collects extra money from his insurance company because the insurance value of the car is greater than its actual value.35

Although some vehicles stolen for export to Mexico might have been stolen for insurance fraud purposes, there are two reasons why insurance fraud would play a smaller part in the United States than in Western Europe, Firstly, car owners in Europe carry insurance that lets them recover the full cost of the car if it is stolen. In the United States, not every comprehensive (full) insurance policy covers car theft, and even if it does, it is still not guaranteed that the owner will receive the full value of the car due to the depreciation of the cars value over time or other factors. Secondly, cars stolen in the United States are rarely expensive luxury models, and car owners in the United States rarely purchase full insurance for non-luxury cars.Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Export Stolen Vehicles

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

- To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

- Your E-mail *

Copy me

- Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.