The Problem of School Vandalism and Break-Ins

This guide addresses school vandalism and break-ins, describing the problem and reviewing the risk factors. It also discusses the associated problems of school burglaries and arson. The guide then identifies a series of questions to help you analyze your local problem. Finally, it reviews responses to the problem, and what is known about them from evaluative research and police practice.

The term school vandalism refers to willful or malicious damage to school grounds and buildings or furnishings and equipment. Specific examples include glass breakage, graffiti, and general property destruction. The term school break-in refers to an unauthorized entry into a school building when the school is closed (e.g., after hours, on weekends, on school holidays).Related Problems

School vandalism and break-ins are similar to vandalism and break-ins elsewhere, and some of the responses discussed here may be effective in other settings. However, schools are unique environments; the factors underlying school vandalism and break-ins differ from those underlying similar acts elsewhere, and therefore must be analyzed separately. Related problems not addressed in this guide include

- Vandalism in nonschool settings

- Graffiti

- Arson

- School theft by students (e.g., of student backpacks and wallets)

- School theft by staff (e.g., of equipment)

- Burglary of retail establishments

- Burglary of single-family houses.

School break-ins typically fall into one of three categories:

- Nuisance break-ins, in which youth break into a school building, seemingly as an end in itself. They cause little serious damage and usually take nothing of value.

- Professional break-ins, in which offenders use a high level of skill to enter the school, break into storage rooms containing expensive equipment, and remove bulky items from the scene. They commit little incidental damage and may receive a lot of money for the stolen goods.

- Malicious break-ins entail significant damage to the school's interior and may include arson. Offenders sometimes destroy rather than steal items of value.1

While school vandalism and break-ins generally comprise many often-trivial incidents, in the aggregate, they pose a serious problem for schools and communities, and the police and fire departments charged with protecting them. Many school fires originate as arson or during an act of vandalism.2 Though less frequent than other types of school vandalism, arson has significant potential to harm students and staff. In the United Kingdom in 2000, approximately one-third of school arson fires occurred during school hours, when students were present, a significant proportional increase since 1990.3

Over the past two decades, concerns about school violence, weapons, drugs, and gangs have eclipsed concern and discussion about school vandalism, its causes, and possible responses. However, even as concerns about student and staff safety from violence have become school administrators' top priority, vandalism and break-ins continue to occur regularly and to affect a significant proportion of U.S. schools. From 1996 to 1997, the incidence of murder, suicide, rape, assault with a weapon, and robbery at schools was very low.4 In contrast, over one-third of the nation's 84,000 public schools reported at least one incident of vandalism, totaling 99,000 separate incidents.5

Graffiti tagging and other forms of defacement often mar school buildings and grounds. Credit: David Corbett

These statistics likely fail to reveal the magnitude of the problem. While the U.S. Department of Education, major education associations, and national organizations regularly compile data on school-related violence, weapons, and gang activity, they do not do so regarding school vandalism and break-ins. One reason for this may be that schools define vandalism very differently—some include both intentional and accidental damage, some report only those incidents that result in an insurance claim, and some include only those incidents for which insurance does not cover the costs.6 School administrators may hesitate to report all cases of vandalism, break-ins, or arson because they view some as trivial, or because they fear it will reflect poorly on their management skills.7 Partially because of the failure to report, few perpetrators are apprehended, and even fewer are prosecuted.8

The lack of consistency in reporting school vandalism and break-ins means that cost estimates are similarly imprecise. Vandalism costs are usually the result of numerous small incidents, rather than more-serious incidents. Various estimates reveal that the costs of school vandalism are both high and increasing.9 In 1970, costs of school vandalism in the United States were estimated at $200 million, climbing to an estimated $600 million in 1990.10 Not only does school vandalism have fiscal consequences associated with repairing or replacing damaged or stolen property and paying higher insurance premiums if schools are not self-insured, but it also takes its toll in terms of aspects such as difficulties in finding temporary accommodations and negative effects on student, staff, and community morale.

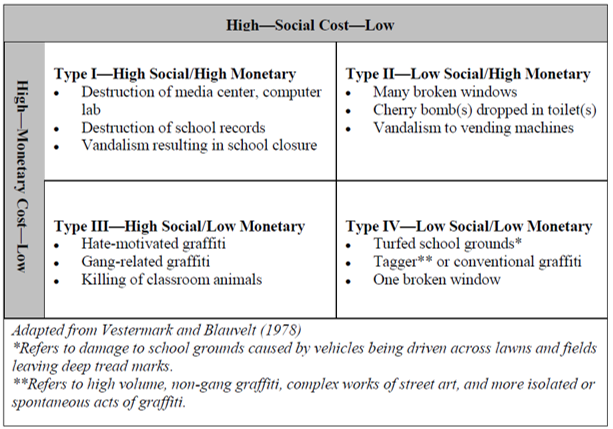

Not all incidents of vandalism and break-ins have the same effect on the school environment. Again, two useful dimensions for understanding the problem's impact are the monetary cost (where the repair charges are high), and the social cost (where the event has a significant negative impact on student, staff, and community morale). Events with high monetary and social costs typically occur less frequently than those with low monetary and social costs.11

Factors Contributing to School Vandalism and Break-Ins

Understanding the factors that contribute to your problem will help you frame your own local analysis questions, determine good effectiveness measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses.

Offender Characteristics

Those who vandalize or break into schools are typically young and male, acting in small groups. Vandalism and break-ins are most common among junior high school students, and become less frequent as students reach high school.12 Those involved in school-related arson are more likely to be in high school.13 Many vandals have done poorly academically, and may have been truant, suspended, or expelled.14 As is typical of many adolescents, students who vandalize and break into schools have a poor understanding of their behavior's impact on others, and are more concerned with the consequences to themselves.15 Offenders are no more likely to be emotionally disturbed than their peers who do not engage in the behavior, nor are they any more critical of their classes, teachers, or school in general.16

While the majority of students do not engage in vandalism, they do not generally harbor negative feelings toward those who do. In other words, "vandalism is a behavior that students can perform without the risk of condemnation by other students."17 Youth who lack full-time parental supervision during after-school hours have been found to be more involved in all types of delinquency than students whose parents are home when they return from school.18 In 2002-2003, 25 percent of all school-aged children were left to care for themselves after school, including half of children in grades 9 through 12 and one third of children in grades 6 though 8.19

Though far less frequently, adults sometimes commit school vandalism and break-ins. Most often, they do so to steal high-value items (e.g., computers, televisions, cameras) and sell them on the street.20 Adults are far less likely to maliciously deface or destroy school property.

Motivations

The typical observer may think school vandalism and break-ins are pointless, particularly when the offenders have focused on property destruction and have taken nothing of value. One can better understand the behavior when considering it in the context of adolescence, when peer influence is a particularly powerful motivator. Most delinquent acts are carried out by groups of youths, and vandalism is no exception. Participating in vandalism often helps a youth to maintain or enhance his or her status among peers.21 This status comes with little risk since, in contrast to playing a game or fighting, there are no winners or losers.

Beyond peer influence, there are several other motivations for school vandalism:

- Acquisitive vandalism is committed to obtain property or money.

- Tactical vandalism is used to accomplish goals such as getting school cancelled.

- Ideological vandalism is oriented toward a social or political cause or message, such as a protest against school rules.

- Vindictive vandalism(such as setting fire to the principal's office after being punished) is done to get revenge.

- Play vandalism occurs when youth intentionally damage property during the course of play.

- Malicious vandalism is used to express rage or frustration. Because of its viciousness and apparent senselessness, people find this type particularly difficult to understand.22

As schools have become increasingly technologically equipped, thefts of electronic and high-tech goods have become more common.23 Computers, VCRs, and DVD players are popular targets because they are relatively easy to resell. Students also steal more-mundane items such as food and school supplies, for their own use.

In addition, youth may participate in school vandalism or break-ins in a quest for excitement.24 Some communities do not have constructive activities for youth during after-school hours and in the summer. Without structured alternatives, youth create their own fun, which may result in relatively minor vandalism or major property damage to schools and school grounds.

Times

A high proportion of vandalism occurs, quite naturally, when schools are unoccupiedbefore and after school hours, on weekends, and during vacationsas well as later in the school week and later in the school year.25 Local factors, such as the community's use of school facilities after hours, may also determine when vandalism is most likely to occur in any one school.

Targets

Schools are prime targets for vandalism and break-ins for a number of reasons:

- They have high concentrations of potential offenders in high-risk age groups.

- They are easily accessible.

- They are symbols of social order and middle-class values.

- Some youth believe that public property belongs to no one, rather than to everyone.

Partially hidden entryways can provide opportunity for would-be vandals. Credit: David Corbett

Some schools are much more crime-prone than others, and repeat victimization is common.26 A school's attractiveness as a vandalism target may also be related to its failure to meet some students' social, educational, and emotional needs; students may act out to express their displeasure or frustration.27 Schools with either an oppressive or a hands-off administrative style, or those characterized as impersonal, unresponsive, and nonparticipatory, suffer from higher levels of vandalism and break-ins.28 Conversely, in schools with lower vandalism rates,

- Parents support disciplinary policies

- Students value teachers' opinions

- Teachers do not express hostile or authoritarian attitudes toward students

- Teachers do not use grades as a disciplinary tool

- Teachers have informal, cooperative, and fair dealings with the principal

- Staff consistently and fairly enforce school rules.29

Certain physical attributes of school buildings and grounds also affect their vulnerability to vandalism and break-ins. In general, large, modern, sprawling schools have higher rates of vandalism and break-ins than smaller, compact schools.30 The modern, sprawling schools have large buildings scattered across campus, rather than clustered together. A school's architectural characteristics may also influence the quality of administrative and teacher-student relationships that are developed, which can affect the school's vulnerability. Common vandalism locations and typical entry points include31

Rooftops that are accessible only from within the building provide a greater degree of security. Credit: David Corbett

- Partially hidden areas around buildings that are large enough for small groups of students to hang out in (which can give rise to graffiti, damaged trees and plants, and broken windows)

- Alcoves created by stairways adjacent to walls, depressed entrances, and delivery docks (which offer coverage for prying at windows, picking locks, and removing door hinges)

- Main entrances not secured by grills or gates when school is closed, and secondary entrances with removable exterior door hardware

- Unsecured windows and skylights

- Large, smooth, light-colored walls (which are prime graffiti targets)

- Rooftops accessible from the ground, from nearby trees, or from other rooftops (which can allow access to damageable equipment and hardware).

Vandals damage schools that neglect grounds and building maintenance, those whose grounds have little aesthetic appeal, and those that do not appear to be occupied or looked after more often than they damage carefully tended and preserved schools.32

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

School Vandalism & Break-ins

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

- To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

- Your E-mail *

Copy me

- Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.