Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Understanding Your Local Problem

You must combine the basic facts provided above with a more specific understanding of your local problem. Analyzing the local problem helps in designing a more effective response strategy.

Asking Key Questions About Graffiti

The following are some critical questions you should ask in analyzing your particular problem of graffiti, even if the answers are not always readily available. If you fail to answer these questions, you may select the wrong response.

Victims

- Whom does the graffiti directly victimize (e.g., homeowners, apartment managers, business owners, transit systems, utilities, public works , others)?

- Whom does the graffiti indirectly affect (e.g., people who see the graffiti)? How fearful are these people? What activities does graffiti affect (e.g., shopping, use of recreational areas and public transit)? (Community or other surveys may be necessary to answer these questions.)

Amount of Graffiti

- How much graffiti is there? (Visual surveys are necessary to answer questions about the amount of graffiti.)

- How many individual tags or separate pieces of graffiti are there?

- How big is the graffiti (e.g., in square feet)?

- How many graffiti locations are there?

- How many graffiti-related calls for service, incident reports or hotline reports are there?

Types of Graffiti

- Are there different types of graffiti? How many of each type?

- What are the content and unique characteristics of the graffiti? (Some agencies photograph or videotape graffiti to create an intelligence database noting key characteristics, to link graffiti to chronic offenders.)†

- What appear to be the motives for the graffiti?

- Is the graffiti simple or complex? Small or large? Single-colored or multicolored?

- Is the graffiti isolated or grouped?

- What do offenders use to make the graffiti (e.g., spray paint, marking pens, etching devices)

† See Otto, Maly and Schismenos (2000) for more information about this technology, as used in Akron, Ohio.

Locations/Times

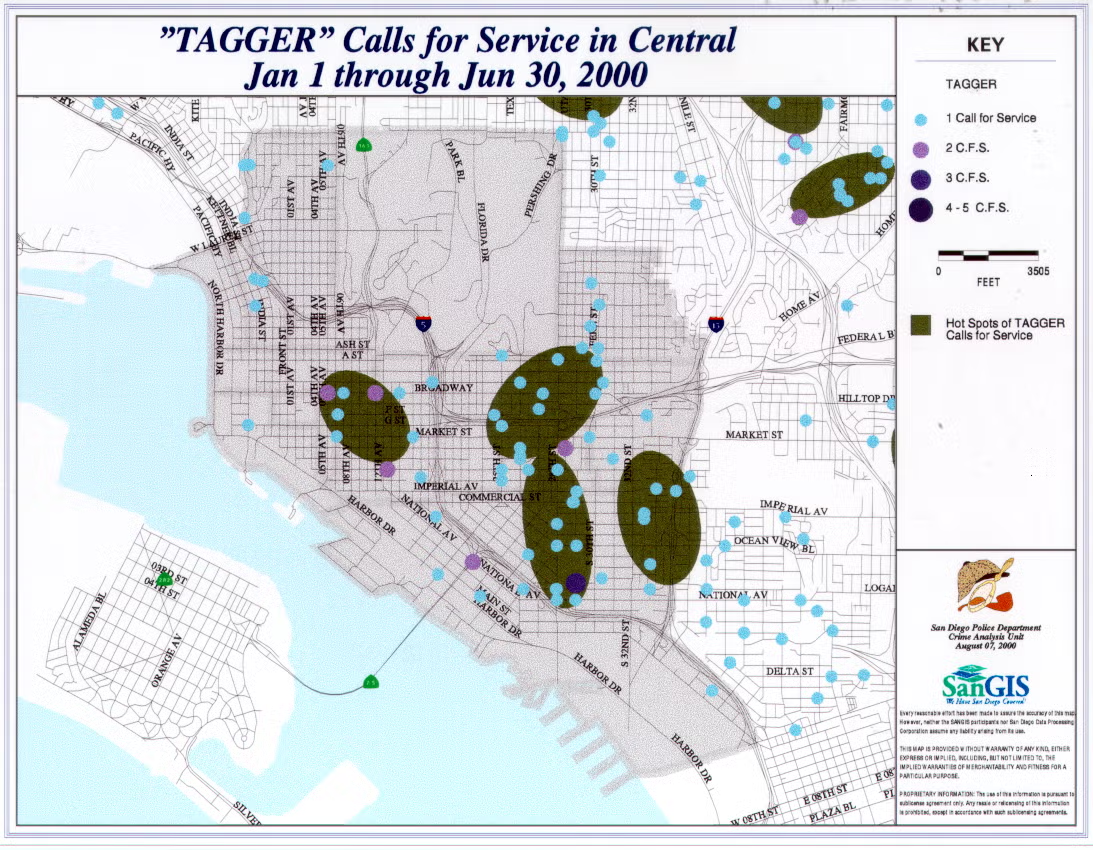

- Where does the graffiti occur? (Maps of graffiti can be particularly illuminating, revealing its distribution across a large area.† See Figure 1.)

- What are the specific locations where the graffiti occurs (e.g., addresses or, more precisely, Global Positioning System locations for sites without addresses, such as in parks or along railroad tracks)?

- How close is the graffiti to graffiti-generators such as schools?

- What are the characteristics of the locations in which graffiti is prevalent? Are the locations residences, schools? Are they close to stores—what type, with what hours—or bus stops—what running times?

- What are the characteristics of graffiti targets? Are the targets signs, walls, fences, buses, trains?

- What are the physical environment's characteristics, including lighting, access, roads, surface types, and other relevant factors?

- When does the graffiti occur? Time of day? (using last known graffiti-free time)? Day of week?

- Do the peak times correspond with other events?

- † Maps of graffiti have been used to map gang violence and gang territory. See, for example, Kennedy, Braga and Piehl (1997) [PDF].

Offenders

- What are the offenders' characteristics (e.g., age, gender, student)?

- Where do the offenders live, go to school or work? How do these locations correspond to graffiti locations and/or police contacts?‡

- What is the pattern of offending? For example, is the graffiti spontaneous or planned, intermittent or regular?

- What are the offenders' motives? (Offenders can be interviewed to collect this information. Undercover investigations, stings, surveillance, and graffiti content analysis can reveal more about offenders' practices.)†

- Are offenders lone operators or part of a group?

- Does drug and/or alcohol use contribute to graffiti?

- Is graffiti associated with other violations, such as truancy?

- ‡ Photographs of offenders and their address information can also be linked to maps.

- † Police in some cities have posed as film crews, interviewing taggers about their practices.

Figure 1. Map showing locations of graffiti

Measuring Your Effectiveness

Measurement allows you to determine to what degree your efforts have succeeded, and suggests how you might modify your responses if they are not producing the intended results. You should take measures of your problem before you implement responses, to determine how serious the problem is, and after you implement them, to determine whether they have been effective. All measures should be taken in both the target area and the surrounding area. (For more detailed guidance on measuring effectiveness, see the companion guide to this series, Assessing Responses to Problems.)

Research shows that graffiti can be substantially reduced, and sometimes eliminated. The following are potentially useful measures of the effectiveness of responses to graffiti. To track possible displacement, such measures should be routine:

- Amount or size of graffiti

- Number and type of graffiti locations

- Content and type of graffiti

- Length of time graffiti-prone surfaces stay clean

- Public fear and perceptions about the amount of graffiti (may be assessed through surveys of citizens, changes in use of public space and transit systems, changes in retail sales, and other indirect measures).

Some jurisdictions track the numbers of arrests made, gallons of paint applied or square feet covered, amount of graffiti removed, or money spent on graffiti eradication;14 these measures indicate how much effort has been put into the anti-graffiti initiative, but they do not tell you if the amount or nature of graffiti has changed in any way.† You should choose measures based on the responses chosen; for example, if paint sales are limited, you should place more emphasis on tracking the type of graffiti tool used. Tools do change; for example, some offenders have begun using glass etching fluid.

† Because many anti-graffiti strategies are quite expensive, a cost-benefit analysis will provide a baseline measure of benefits associated with specific costs of different strategies.

It is widely believed that graffiti is easily displaced,‡ but evidence of such displacement is scant. The notion that graffiti is an intractable problem that is easily displaced has been fueled by haphazard and piecemeal crime prevention measures.15 Useful measures of graffiti will assess the extent to which graffiti is reduced or moved to different locations, or reflect a change in offenders' tactics. While graffiti offenders can be persistent and adaptive, there is no reason to assume that displacement will be complete; indeed, successful responses may have a widespread effect.

‡ The response to graffiti in the New York subway system resulted in some reported displacement to buses, garbage trucks, walls, and other objects in the city (Butterfield 1988; Coffield 1991).

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Graffiti

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.